Croatia

Flag of Croatia | |

| Capital | Zagreb |

| Inhabitants | 4,486,881 |

| Language(s) | Croatian |

In 1918, the Croats, Serbs, and Slovenes formed a kingdom known after 1929 as Yugoslavia. Following World War II, Yugoslavia became an independent communist state under the strong hand of Marshal TITO. Although Croatia declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, it took four years of sporadic, but often bitter, fighting before occupying Serb armies were mostly cleared from Croatian lands. Under UN supervision the last Serb-held enclave in eastern Slavonia was returned to Croatia in 1998.

Contents |

History

Alhough Croatia developed under the impact of many different cultures - Greek, Roman, Celtic, Illyrian, Austrian, Hungarian, Byzantine, Islamic - it gave its own and unique imprint to the history of Europena civilization.

See Prehistoric Archaelology in Croatia.

Let us first give a very rough sketch of the main historical periods of the Croatia's past:

- the arrival of the Croats to the Balkan peninsula at the beginning of the 7th century,

- the period of Croatian dukes and kings of native birth (until 1102),

- Croatia sharing with Hungary a new state under common Hungarian and Croatian kings (1102-1526),

- Croatia ruled by the Habsburgs, as a member of the Habsburg Crown (1527-1918, Austro Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918), parts of Croatia under Venice, Turkish Ottoman Empire and France,

- Croatia in the first Yugoslavia (1918-1941),

- The Independent State of Croatia (1941-1945),

- Croatia as a republic in Tito's (or second) Yugoslavia (1945-1991),

- internationally recognized Republic of Croatia (January 1992).

Croatia is a point of contact of very different cultures and civilizations. Across its territory or along its boundary

- the border between Western and Eastern Roman Empire had been laid by the Roman Emperor Theodosius in 395,

- the border between Francs and Byzantium (9th century),

- between Western and Eastern Christianity (11th century),

- and between Islam and Christianity (15-19th century).

The origins

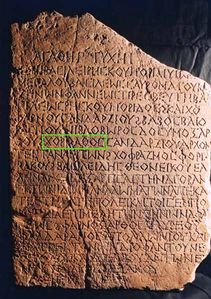

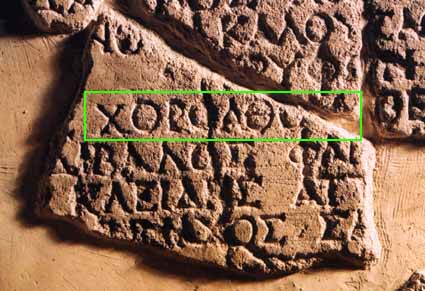

The origins of the Croatian name are Iranian. The earliest mention of the Croatian name as Horovathos can be traced on two stone inscriptions in Greek language and script, dating from around the year 200, found by the Black Sea (more precisely in the seaport Tanais on the Azov sea, Krim). Both tablets are held in the Archeological museum in St Petersburg, Russia.

One of the confluents to Don river near the region of Azov is called Horvatos (see [Pascenko], p. 87). The Croatian name can be traced to different sites in Ukraine, also around Krakow in Poland, in Bohemia, and Austria, thus showing migrations of the Croatian tribes to their future homeland.

In the "Bavarian geographon" (written in 666-890) there is a description of various tribes in the north of Karpatian and and Sudetian mountains, where the Croats are also mentioned.

In the region of northern Steiermark, Austria, (between Judenburg and Leoben) there is a place called Kraubat. The name appears many times in various charters of the 11th and 12th centuries, and is written as Chrowat (= Croat).

In the region of Kärnten (old Karantia in the south of Austria) there is a place called Kraut, also derived from the Middle Age name Chrowat, mantioned in many charters of the 11th and 12th centuries.

In Kärnten (Karantia) there existed a Croatian parish already in the 10th century. Old manuscripts call it pagus Crouuati, which is obviously derived from the Croatian name (= Croatian parish). The name appears even in Royal charters. According to investigations of Felicetti this parish of `pagus Crouuati' spread precisely along the Gosposvetsko polje, where the earliest Slavic Dukes of Karantia had a seat. It included also the region of today's Klagenfurt (Celovec), capital of Karantia, together with the famous Church of Gospa Sveta (Maria Saal, Maria in Solio, Maria ad Karanten), probably the oldest Christian church in the region. The above information regarding the Croats in Austria are taken from Ferdo Sisic, one of the greatest Croatian historians.

White Croats

Constantine Porphyrogenitus (905-959), a Byzantine emperor and writer, mentions the state bearing the name of White Croatia. His description shows that it occupied a wide region around its capital Krakow, in parts of Bohemia, Slovakia, and Poland. The state disapeared in 999. St. Adalbert (Vojtech, 10th century) was a descendant of the White Croats, son of the White-Croatian duke Slavnik. He was spreading Christianity, education and culture, and to this end founded the benedictine monastery in Brevnov in 993. Also St. Ivan Hrvat, who died in Tetin in Bohemia in 910, was a son of White-Croatian King Gostumil. It is interesting to add that according to some American documents from the beginning of this century there were about 100,000 immigrants to the USA born around Krakow (Poland) who declared themselves to be Bielo-Chorvats, i.e. White Croats by nationality. See US Senate-Reports on the Immigration commission, Dictionary of races or peoples, Washington DC, 1911, p. 40, 43, 105.

Even today the descendants of the White Croats live in Bohemia. The surname Charvat is still rather widespread there. For example a director of the National Theatre Opera in Praha in 1990's was Mr Premysl Charvat. An outstnding person in part of Prague called Nove Mesto was Jan Charvat (+1424). In the same quarter of Prague there is a street called Charvatska street even today. Villages in Bohemia like Harvaci, Harvatska gorica reveal its early Croatian inhabitants.

According to the Prague Telephone Book 1999/2000 there are as many as 516 individuals having names of possible Croatian root:

- Charvat and Charvatova (380, several pages...),

- Chorvat and Chorvatova (10),

- Chorvatovicova (1),

- Horvat (21),

- Horvath and Horvathova (79),

- Horvatik and Horvatkova (14),

- Horvatovic and Horvatovicova (2),

- Krobath (1),

- Krobot and Krobotova (8).

CONCLUSION: Since the capital of Bohemia today (in 2000) has about 1,250,000 inhabitants, than assuming that each telephone subscriber has at least three closest relatives in the mean, we obtain that in a random set of 800 Prague citizens there will be at least one with Croatian name. Many thanks to my dear friend Mr. Vlatko Bilic for painstaking counting :)

The Slavnik family had its coins with inscription Mulin Civitas, issued by Duke Sobjeslav (?-1004), the oldest son of Slavnik. This confirms that the fortress of Mulin near Kutna Hora (west of Prague in Bohemia) was a part of their territory. It is assumed that the Slavnik's were the leading tribe of the Croats in the 10th century in that region. Their main seat was in the town of Libica, west of Prague (near Kutna Hora). Thus we had two parallel Croatian states in that period: White Croatia in Central Europe and Dalmatian-Panonian Croatia near the Adriatic sea.

In 995, when White Croatian troops led by Sobjeslav were defending their Dukedom from pagan tribes, White Croatia was suddenly attacked by the Czech duke Premysl, destroying their capital Libice and killing most of the Croatian population. There are some conjectures that several noble families in Poland (like Paluk's) are descendants of White Croats, as well as the family of Rozomberk (which seems to be related to the town of Ruzomberok in Slovakia). Sobjeslav was killed in 1004 on a bridge over Vltava river in Prague, when Polish troops tried to occupy the city. See Ivica Sumic: U potrazi za "Hrvatskom Atlantidom" (In the quest of "Croatian Atlantida"), Stecak, Sarajevo, No 64, 1999.

The name of the Croats is met in many places throughout Ukrainian soil. It is contained in Ukrainian written documents since the 2nd century until the end of the 10th century. The famous Ukrainian chronicler Nestor from Kiev (in his "Povest vremennyh let", 1113) mentioned also the White Croats inhabiting early-medieval Old-Ukrainian empire, known as the Kiev Rus'. According to a very old legend, one of the three brothers who founded the Ukrainian capital Kiev was Horiv, whose name might be at least hypothetically related to the Croatian name: Horvat. Even today some of the Ukrainian citizens say for themselves to be the White Croats. There are many proofs that the Croats once lived in common with Ukrainian and Slovak people: their language (very widespread ikavian dialects in Croatia and Slovakia, ikavian language in Ukraine), legends, customs, many common toponyms etc.

The region of historical Pagania around the Neretva river has many common toponyms and hydronyms with Western Ukraine, like Neretva, Mosor, Ostrozac, Gat. Also Sinj, Kosinj, Kostrena, Knin, Roc, Modrus, and many other throughout Croatia and Western Bosnia. Too many to be just an incidence.

There are numerous names of villages, hills and rivers in Slovakia, Czechia (especially in Moravia), Poland and Ukraine, which have their obvious equivalents in Croatia and Bosnia - Herzegovina. Many of them are indeed surprising:

Bac, Bajka, Baska, Bila, Bistrice, Blatce, Bohdalec, Boskovice, Brezovica, Budin, Budisov, Cehi, Chrast, Chvojnica (= Fojnica), Dol. Krupa, Dolni Lomna, Dolni Domaslovice, Doljani, Doubrava, Doubravice, Doubrovnik, Drienovac, Gat, Harvatska Nova Ves, Hor. Mostenice, Hradec, Hvozd (Gvozd), Javornik, Kal'nik, Klenovec, Klenovice, Klobuky, Kninice, Konice, Koprivnice, Kostelec, Krasno, Kuhinja, Lipa, Lomnice, Ljubica, Mali Javornik, Markusovce, Nova Ves, Novosad, Odra, Okruhlica, Parac, Plesivec, Pohorelice, Porin, Raztoka, Rogatec, Ribnik, Rudina, Selce, Slatina, Sopotnia, Stitary, Sumperk, Tabor, Tajna, Travnik, Trebarov, Trzebinia, Tucapy, Veliki Javornik, Vinica, Vinodol, Vrabce, Vrdy, Vrbovec, Zabreh, Zubak, Zumberk.

The once prosperous and rich Ukrainian village of Horvatka near Kiev (note well: Horvat = Croat) disappeared overnight in 1937, together with all of its inhabitants, during Stalin's infamous collectivization, sharing the tragic destiny of millions of Ukrainians. The only witness is an innocent brook, called Horvatka even today. In the 1990s in Kiev, Ukraine, a youth organization of scouts was founded, and named - White Croat (Bili Horvat; reported by Croatian ambassador Gjuro Vidmarovic in 2000)!

In the north of Croatia there is a very small village called Velika Horvatska (Great Croatia!), and a small brook bearing the same name. It reminds us about existence of White Croatia. We find it pertinent to mention that we know of several cases during former Yugoslavia in which young Croatian soldiers were not allowed by Serbian officers to declare that they were born in the village called Velika Horvatska, but were pressed to declare a nearby village Zbilj.

Old Norwegian - Viking travel writers Sigurd, Ohtere, and Wulfstan from the 8th century mention the Kingdom of Krowataland on the territory of today's Ukraine. It has been investigated by a Czech historian and writer Karel Krocha.

The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610-641) asked the Croats from White Croatia for help in protecting his Empire from the penetration of the Avars. As written by Byzantine Emperor Constantin Porphyrogenetus from the middle of the 10th century, a part of the White Croats, led by two sisters Buga and Tuga,and five brothers Kluk, Lobel, Muhlo, Kosjenc, Horvat, moved to the territories of present-day Croatia. This happened in the 7th century. There they came in touch with the Romans and romanized descendants of Illyrians, Celts and others.

Soon after their arrival in the 7th century they were baptised and so accepted Christianity. The Croats were the first among the Slavs who converted to Christianity.

According to Byzantine ruler Constantin Porphyrogenetus, the Croats made an agreement with the Pope Agaton as early as in 679, in which they obliged themselves not to undertake any offensive wars against neighbouring Christian states. This was the first international diplomatic agreement of the Croats with the Holy See. The importance of this event has been pointed out by the Pope John Paul II in his speech held in the Croatian language during his apostolic visit to Croatia in Zagreb in September 1994. The Pope also stressed the importance of more than 13 centuries of Christianity among the Croats.

Pope John Paul II had his second apostolic visit to Croatia in 1998, on the occasion of beatification of Cardinal Alojzije Stepinac.

The Roman Empire was divided in 395. Later the Croats entered the Western Roman Empire. The historical border between the Eastern and Western Roman Empire was the river Drina. It flows between present Serbia and Bosnia, and in the past it divided in political and cultural sense, two very different civilizations, which had been separated until the penetration of the Turks in the 16th century. Later in 1054 this division also defined the border of the two Churches, one under Byzantium (Constantinople) and the other under Rome. Let us mention that Montenegro and Albania belonged to the Western Church. In 1184 the Serbian Orthodox Church penetrated by military expansion to Montenegro. Until that time the territory of Montenegro was a part of Red Croatia. Serbia, and later Montenegro, developed on the heritage of the Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantine Empire).

According to Bulgarian scientist Gantscho Tsenoff (1875-1952), professor at the university of Berlin, the founder of Bulgarian state in the first half of the 7th century was KROVAT (or KURVAT). Tsenoff points out that this reveals very early and interesting connections between Bulgarians and Croats. The third son of Krovat was Asparuh, a well known name in Bulgarian history. See Ganco Cenov: "Krovatova B'lgaria i pokr'stvaneto na B'lgarite", Plovdiv 1998, in particular pages 59 and 183 (the first 1937 edition was forbidden during the communist period).

The earliest Croatian dukes and kings

The earliest known Croatian duke was Borna, who ruled from around 812 to 821.

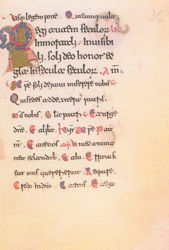

Duke Trpimir ruled from 845 to 864. In 852 he issued the oldest known governmental document in the Latin script, where the Croatian name was mentioned (dux Chroatorum). The fact that his name is recorded in the Cedad Gospels (from today's Italian city Cividale) shows the cultural level of his state. The most famous Benedictine monk Gottschalk found refuge at the Croatian court from 846 to 848. Trpimir invited the Benedictines, known as great promoters of education and economy. One of the earliest Benedictine monasteries was built in 852 near Split. In the 11th century Croatian Benedictines had more than 40 monasteries, mostly along the Adriatic coast. They contributed a great deal to the cultural and material development of the Croats. On the photo you can see a choir screen panel from Split, containing pentagram and nice interlace patterns, 11th century.

Besides the name of Trpimir also the names of some other Croatian dukes can be seen in Cedad Gospels: Branimir, Braslav, their wifes, and escort.

In 871 the King of Italy Ludovic II and Byzantine Emperor Basil I defeated the Arabs in the city of Bari (Italy). Croatian soldiers also participated in the battle, arriving to Bari on Dubrovnik ships.

Some of the earliest Benedictine monastaries in Croatia were founded in

- Karin, 850,

- Bisevo on the island of Vis, 850,

- Rizinice (near Split), 852,

- Zadar, St Krsevan, 908,

- Nin, St Ambrosius, 941,

- Nin, St Maria, 948,

- Ugljan (on the island of Ugljan near Zadar), 988,

It is little known that the name of the island was in fact ULJAN (derived from the Croatian name for oil - ulje). Namely, according to Italian ortography it was transcribed as Uglian, Ugliano (gli = lj). It is interesting that both names Uljan and Uglian(o) can be seen on old maps of the island. Of course, the Croatian name ulje (as well as the English oil) is of Latin origin.

The Croatian Duke Branimir made further steps in strengthening the relations with Rome. During the solemn divine service in St. Peter's church in Rome in 879, Pope John VIII gave his blessing to the duke and the whole Croatian people, about which he informed Branimir in his letters. In his letter dated from 881 the Pope addressed Branimir as the `glorious duke'. This was the first time that the Croatian state was officially recognized (at that time the international legitimacy was given by the Pope). In Branimir's time Venetians had to pay taxes to the Croatian state for their ships traveling along the Croatian coast.

The earliest dukes and kings we know of lived in the 9th and the 10th century (see a figure of an unknown Croatian Dignitory). The strongest among them was King Tomislav, who ruled from from 910 to 928. The previously mentioned Constantine Porphyrogenitus, a Byzantine emperor, referred to him as the Croatian King. In his time Croatia was one of the most powerful states in Europe. It had an enormous (for that time) army of 100,000 foot-soldiers and 60,000 horsemen, 80 larger and 100 smaller ships. When Bulgaria occupied Serbia in 924, King Tomislav accepted and protected many Serbs who had escaped and sought refuge in the Croatian state. The Bulgarian tsar Simeon soon tried to spread his reign to Croatia, but Tomislav defeated him in 927. The Serbs organized their earliest internationally recognized Kingdom in 1217.The Arabs began to attack the Croatian coast in the 9th century. So a Croat from Dalmatia, known under the Islamic name Djawhar ben Abd Allah (911-992), was taken as a slave to the court of caliph Al-Khaim in Tunisia. Later he made a great career becoming the supreme general. He conquered the land of pharaos, thus extending the Empire of Fatimids from the shores of the Atlantic to the river Nile. He founded the new Egyptian capital Al-Qahira (Cairo), the future second largest Islamic city after Baghdad. In 970 he built up the mosque named Al-Azhar (the Brightest).

A very old mention of the name of HORITS, the ancient name of the Croats (Horvat), can be found in the Latin work ``Historia adversus Pagano by Paulus Orosius (9th century). Its translation into Old English has been made by King Alfred (871-901).

As is well known, many important monuments of pre-Romanesque Croatian art have been found in the region of Knin which used to be the residence of Croatian kings (11th century). Here are two examples, both from the 9th century.

- In this grave rests famous Jelena, wife of King Michael (Kresimir), mother of King Stephen (Drzislav). She brought peace to the Kingdom. On the eighth day of October 976 from the incarnation of Our Lord she was buried here in the 4th indiction, 5th lunar cycle, 17th epacta, 5th solar cycle. While she lived she was mother of the kingom and she became mother of the poor and protectress of widows. You who look here say: God have mercy upon her soul.

An important monument is a stone panel from the 10th century mentioning the name of DUX CHROATORUM Drzislav, a son of queen Jelena. It contains nicely interlaced interlace patterns.

Probably the greatest achievement of Croatian Pre-Romanesque sculpture is choir screen panel from the Church of St. Domenica (Sv. Nediljica) in Zadar, with scenes of the Massacre of the Innocents and the Flight to Egypt, created in the 11th century (André Malraux included it into his "Musée imaginaire"). The Croats were deeply devoted to the Western Church. When Pope Alexander III visited Zadar in 1177, one of the most beautiful European cities, he was solemnly greeted by people singing very old songs in their Croatian language (as noted by Italian chronicler Baronius):

- "...immensis laudibus et canticis altissime resonantibus in eorum Sclavica lingua."

There is no doubt that this was Croatian glagolitic singing (see an article by dr. Marija s. During the shameful aggression of Venetians and Crusaders in 1202, the Christian city of Zadar, a dangerous rival of Venice at the time, was robbed and terribly destroyed. Geffroy de Villehardouin, a French chronicler who described the siege and destruction of Zadar for the good of Venice during the Crusade, wrote that Zadar in Sclavonia (a synonym of Croatia at that time) is one of the best fortified cities, surrounded with strong walls, and that it is difficult to find a more beautiful, better fortified and richer city. The City was again destroyed

- in the Second World War; carpet-bombed 72 times by Anglo-American air-forces by the end of 1943 and in the beginning of 1944, including its historical centre, with great human and material losses. WHY? We still do not know. The City had no military importance.

- bombed during the Greater Serbian aggression in 1991-95, and for long periods without water and electricity.

Dalmatian rounded beneventana that was in use in the Zadar scriptorium of St Krsevan shows original characteristics different from the south-Italian round beneventana.

The church of St. Simun in Zadar possessed an old codex written in Latin script, containing well known lauds from12th century. Zadar had a famous scriptorium at that time. The book dissapeared by the end of 19th century, and since 1893 is held in Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. Numerous Croatian valuables are held throughout Europe. See a list of Glagolitic books and manuscripts only, held outside of Croatia. Pre-Romanesque architecture in Croatia is described in detail in works of [Delonga].

It is interesting that King Richard the Lion-Hearted (1157-1199) sojourned in Zadar (and not in Dubrovnik as it has been believed). Also Henry of Lancaster, the future King Henry IV, visited Zadar and Dubrovnik during his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1392 and 1393. .

In the 12th century the famous Arabian geographer al-Edrisi was working at the court of the the Norman King Roger II in Palermo. After 15 years of study he prepared a huge map of Europe (3.4x1.5 m) where bilad = land, country, and garuasia = Croatia. The map appeared in 1154, when many contemporary countries still do not exist in Europe. Especially important is a description of GARUASIA in the accompaning book of commentaries, where he states that Croatia starts with Istrian cities of Umag, Novigrad, Porec, Rovinj, Pula, Medulin, Labin, Plomin. Then al-Edrisi describes the cities from Bakar to Dubrovnik. It is known that he visited Senj, Knin, Biograd and some other Croatian cities. The original map is kept in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, while partial copies can be found in Paris, St Petersburg, Constantinople and Kairo.

Very important historical source for early Croatian history is Libellus Gothorum, a chronicle from 12th century known in Croatia as Ljetopis popa Dukljanina and Croatian Chronicle. It was written by Archbishop Grgur of Bar (a city in Boka kotorska, a region annexed to Montenegro in 1945), born in Zadar. The chronicle represents the oldest historiographic work of Croatian Middle Ages. There exist two versions, Croatian and Latin. Especially important is Grgur's presentation of assembly (SABOR) on the Duvno field ("in planicie Dalme"), and above all his terms for Croatian territories:

CROATIA ALBA (White Croatia), and CROATIA RUBEA (Red Croatia).

The source Sclavorum Regnum, known as Ljetopis popa Dukljanina and Croatian Chronicle, is also the earliest known literal text written in Croatian language. Marko Marulic translated this chronicle from Croatian into Latin in 1510, and the manuscript is held in Belgrade. The title is

- REGVM DALMATIE, ET CROATIAE HISTORIA VNA CVM SALONARVM DESOLITIONE

Another version is written in Croatian, and in Latin script, due to Jerolim Kaletic from 1546, held in the Vatican. It is a copy of Dmine Papalic's copy of Croatian Chronicle. There are clear indications that the original was written in the Glagolitic script (the opinion goes back to Franjo Racki, and is further supported by Muhamed Hadzijahic from Sarajevo and by Ivan Muzic from Split). For more details see a monograph [Hrvatska kronika 547.-1089.] and the references therein. It is interesting that Shakespeare's The Tempest has its source in Ljetopis popa Dukljanina.

Toma Arcidiakon (Thomas arhidiaconus Spalatensis, 1200-1268), an important chronicler from the city of Split, wrote in his Historia Salonitana that (a part of) Croatian tribes arrived to their present day homeland not as pagans, but as Aryan Christians (though very rude):

- Quamvis pravi essent et feroces, tamen christiani erant sed valde rudes, Ariana etiam erant tabe respersi.

That is why in Croatian history we do not know of any single and precise date of christianisation, as in the case of other European nations, like Ukrainians, Czechs, Bulgarians etc. It seems that we can speak only about conversion of parts of newly arrived Croatian Aryan Christians to Catholicism in their new homeland. Indeed, Toma Arcidiakon writes the following:

- Posteaquam per praedicationem praedicti Johannis et aliorum presulum salonitanorum duces Gothorum et Chroatorum ab Ariane heroseos fuerant contagione purgati.

Henry S. Hart in his book "Venetian Adventurer Marco Polo" (Oklahoma, 1967) states that Marco Polo was a "descendant of an old Dalmatian family which had come from Sibenik, Dalmatia, and settled in Venice in the 11th century". Hart also claims that "crews of the Venetian ships were freemen, so many of them Slavonians (Croatians) from the Dalmatian coast that the long quay by St. Mark's was and is known as the Riva degli Schiavoni (or Riva od Hrvatov in Croatian sources). It is said that Marco Polo had a home on the island of Korcula in Dalmatia. His coat of Arms includes four chickens. And in Italian, Polo (pollo) means chicken or fowl, while in Croatian Pilich means chicks or chickens, which was probably his original name. See [Eterovich]. Eterovich cites about 20 references (mostly Italian, and also English and German, the oldest one being from 1522), claiming the Dalmatian roots of Marco Polo, either from the city of Sibenik or from Korcula, at that time under Venice. See also Marko Polo = Marko Pilich? on this web-site.

Venice was very important place for publishing books of numerous Croatian writers, philosophers and scientists. It is no surprise that in 17th century a Venetian master Bartol Occhi published a catalogue of Croatian books, in which the central Venetian pier (Riva degli Schiavoni) was called Riva od Harvatou, and the catalogue was sold in his workshop in this very street. Precisely in front of the grand hotel Danieli Excelsior in this pier, there is an inscription (hardly legible) showing that this part of Venetian harbour had been reserved for ships from islands of Hvar and Brac: FINE DI STAZIO DEI ABITANTI DELLA BRAZZA E DI LESINA (Lovorka Coralic).

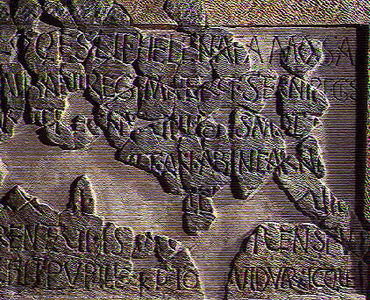

Another important Benedictine monastery, unfortunately almost totally ruined, built probably in the 11th century, is the one in Rudine (Western Slavonia, near Pozega). A sensational discovery were the exotic human-like figures (like on the photo) and some glagolitic inscriptions. Professor Andjela Horvat, historian, discovered stone inscription with BRAT IAN, from 12th or 13th centuries. This is the oldest known Latin inscription in the Croatian lanaguage.

From 1102 the Croats had shared together with Hungarians a newly built state under common Hungarian and Croatian kings. The kings were crowned twice: with the Hungarian and the Croatian crown. From that time on, the Croats were dreaming about having their own independent state, and it was revived after almost nine centuries in 1991.

During this very long period parts of Croatian soil were dominated by Venetians, Italy (in the first half of the 20th century), the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburgs. Among all the nations reigned by the Habsburgs (Czechs, Poles, Slovenians and others) the Croats are together with Austrians and Hungarians the only ones who have preserved an uninterrupted continuity of their state since the Early Middle Ages. Furthermore, as stated by one of best Croatian historians Vjekoslav Klaic, the Croatian Kingdom was the oldest one in the Habsburg Monarchy, older than Austrian, Hungarian, or Czech Kingdom.

During many centuries the Croats had their bans (viceroys) and their assembly called Sabor. The oldest known Sabor was held in Split in 925 and in 928 (devoted more to religious than to secular questions), and in 1076 when Dmitar Zvonimir was elected the Croatian king by the ``unanimous choice of the clergy and the people. The Croats preserved these important state institutions of ban and Sabor also when they decided to enter the Habsburg state (1527--1918). Today the Sabor has the meaning of the Croatian Parliament.

It is interesting that Dante Alighieri (13/14th centuries) mentions the Croatian pilgrims to Italy in his Divine Comedy (Paradiso XXXI, 103-108):

Qual è colui che forse di Croazia

viene a veder la Veronica nostra

che per l'antica fame non sen sazia,

ma dice nel penser, fin che si mostra

"Segnor mio, Gesù Cristo, Dio verace,

or fu sì fatta la sembienza vostra?"

It seems that Dante traveled through Croatia with Croatian Bishop Augustin Kazotic.

It would be difficult even to trace interesting historical personalities that connect the Croats with other nations. So Ivan VI Frankapan was a master of the Royal Palace Stäkebórg, and also led the entire estate of the Royal Court in Sweden. He lived there from 1427(?) until 1433, and was a close friend to Eric VII of Pomerania, the second common King of Denmark, Sweden and Norway. How did Ivan VI get there? Well, when King Eric VII travelled to the Holly Land in 1424, he also passed through parts of Croatia. His travel back to his homeland also led him through Croatian lands. It is known that he visited Dubrovnik, Omis and Senj. It was probably in Senj that King Eric VII met Ivan VI, and made friends with him. Ivan VI Franakapan became known in Sweden as Johann Valle or Jany Franchi. During an uprising of Swedes against the Danish authorities, led by Engelbreksston, Ivan VI was at the Royal Palace. Upon his return to Croatia he became the Ban (viceroy) of Croatia. I owe this information to dr Petar Strcic, director of the Archives of HAZU (Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts).

Very important personality in Croatian history is Ban Josip Jelacic (1801, Petrovaradin - 1859, Zagreb). We offer you quite interesting presentation of the Jelacic family (in French).

From 1918 to 1929 Croatia was one of the states in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians. In 1929 it was renamed Yugoslavia and existed as such until 1941 and as a communist state from 1945 to 1991. The Croats are despite all the difficulties the only ones among all the nations of former Yugoslavia whose state has had uninterrupted continuity since the ninth century.

The territory of former Yugoslavia (named so in 1929) was a point of contact of three very different worlds in its past:

- the Catholic West,

- the Orthodox East,

- and Islam.

Only Slovenia, situated to the west of Croatia, was relatively safe from the threat of Orthodox Christians and Islam. This is why the Republic of Slovenia was nationally the most compact and economically the most developed region in former Yugoslavia. Please, note the difference between Slovenia, Slovakia and Slavonia, which is a part of Croatia. The origin of all these names is the same - derived from the name of SLOVO (= word), from which then the names of Slovinje, Slovinci, Sloveni, Slovenci, Slovani, Slaveni were coined.

It is lovely and amusing to see how in Slovak language one sais "Slovenian - Slovakian dictionary": Slovinsko - Slovenski slovnik. And in Slovenian language, the same would be Slovensko - Slovaski slovar!

In Slovenian part of Istria, near Italian border (south of Trieste) there is a small town of Hrvatini (= the Croats). It is indicative that the most widespread second name in Slovenia is Horvat (= Croat). The Croats living for centuries in present-day Slovenia do not have the status and rights of national minority, contrary to much smaller national minority of Slovenians in Croatia.

Srb is a small village near the spring of the river Una (north of Knin). Serbian linguists see this name as a trace of the Serbian name (Serb->Srb?). However, according to academician Petar Simunovic the name of Srb originates from an old Croatian verb serbati, srebati = to sip, from which the noun "srb" has been derived. Thus "srb" denotes the spring of river Una, where the village lies. Compare with the villages of Srbani (near Pula), and Srbinjak, both in Istria, which clearly have nothing to do with the Serbian name. The Istarski razvod from 13th century mentions the name of srbar, meaning a water spring.

Culture

Art

Twentieth century sculptor Ivan Mestrovic is the pride and joy of Croatia's art world. His work can be seen in town squares throughout the country, and he has also designed several imposing buildings, including the Croatian History Museum in Zagreb. Croatian literary figures include 16th century playwright Marin Drzic and 20th century novelist, playwright and poet Miroslav Krleza - the latter's multi-volume work, Banners, is a saga about Croatian life at the turn of the 20th century.

Religion

Croats are overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, while virtually all Serbs are Eastern Orthodox. In addition to various doctrinal differences, Orthodox Christians venerate icons, let priests marry, and couldn't care less about the Pope. Thoroughly suppressed during Yugoslavia's communist period, Roman Catholicism is now making a comeback, with most churches strongly attended every Sunday. Muslims make up 1.1% of the population and Protestants 0.4%. There's a tiny Jewish population in Zagreb.

Food

Croatians love a bit of oil, and among the greasy delicacies you'll find here are burek, a layered pie made with meat or cheese, and piroska, a cheese donut from the Zagreb region. The Adriatic coast excels in seafood: regional dishes include scampi and Dalmatian brodet (mixed fish stewed with rice). Inland look for specialities such as manistra od bobica (beans and fresh maize soup) or struki (baked cheese dumpling).

Virtually every region produces it's own varieties of wine.

Music

The music of Croatia, like the country itself, has three major influences: the influence of the Mediterranean especially present in the coastal areas, of the Balkans especially in the mountainous, continental parts, and of central Europe in the central and northern parts of the country.

Folk music

The traditional music of Croatia is mostly associated with tamburitza and gusle songs. Tamburitza music, a form of folk music that revolves around the tambura is primarily associated with the northern part of the country while the gusle music became mostly popular in southern (Dinaric) region of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Slavonian town Pozega hosts a known folk music festival, Zlatne zice Slavonije (Golden strings of Slavonia), which has prompted musicians to compose new songs with far-reaching influences, recently including American bluegrass.

Tamburitza became increasingly popular in the 1800s, and small bands began to form, paralleling similar developments in Russia, Italy and the Ukraine. It is sometimes said that the first sextet of tambura players was formed by Pajo Kolaric of Osijek in 1847.

Traditional tamburitza ensembles are still commonplace, but more professional groups have formed in the last few decades. These include Ex Pannonia, the first such group, Zdenac, Berde Band and the modernized rock and roll-influenced Gazde.

In comparison to tamburitza music, which is mainly focused on common themes of love and happy village life, the gusle music is primarily rooted in the Croatian epic poetry with emphasis on important historical or patriotic events.

By glorifying outlaws such as hajduks or uskoks of the long gone Turkish reign or exalting the recent heroes of the Croatian War for Independence, the gusle players have always kept Croatian national spirit alive bringing hope and self-confidence to the enslaved nation. Andrija Kacic Miosic, a famous 18th century author, had also composed verses in form of the traditional folk poetry (deseterac). His book "Razgovor ugodni naroda slovinskog" became Croatian folk Bible which inspired numerous gusle players ever since.

As for contemporary gusle players in Croatia, one person that particularly stands out is Mile Krajina. Krajina is a prolific folk poet and gusle player who gained cult status among some Conservative groups. There are also several other prominent Croatian gusle players who often perform at various folk-festivals throughout Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Although some fans of tamburitza claim that the tambura is the most commonly used ethnic instrument in the United States, the first sound recordings of the Croatian instruments on the American soil were in fact those of gusle and misnica performed by Peter Boro in California in 1939.

Other folk traditions

The folk music of Zagorje, an area north of Zagreb, is known for polka and waltz music similar to the neighboring Slovenia and Austria.

The folk music of Medimurje, a small but distinct region in northernmost Croatia, with its melancholic and soothing tunes became the most popular form of folk to be used in the modern ethno pop-rock songs.

The Dalmatian coast on the other hand sports a cappella choirs known as klape, usually composed of up to a dozen male and female singers, singing typically Mediterranean tunes like in Italy.

In Istria, native instruments like sopila, curla and diple make a distinctive regional sound.

Pop and rock

Pop music and rock is more popular in Croatia than folk music, albeit the folk/pop combinations fare the best. Singers such as Oliver Dragojevic, Ivica Serfezi, Doris Dragovic, Severina, Gibonni and many others base their sound on the traditional sound of the regions they're from.

Among the folk-pop artists, many combine the oriental sound more commonly associated with the folk music of Bosnia and Serbia with the more traditional melodies of Croatia and Dalmatia. Among them are divas like Doris Dragovic and Severina, while the men like Vuco or Thompson are a trademark of perhaps the most oriental sound in Croatia.

Beginning in the late 1980s, folk-rock groups also sprouted across Croatia. The first is said to be Vjestice, who combined Medimurje folk music with rock and set the stage for artists like Legen, Lidija Bajuk and Dunja Knebl.

More vanilla, but nevertheless very popular rock bands in Croatia include Parni Valjak, Crvena Jabuka, Leteci Odred and others.

Croatian record companies produce a lot of material each year, if only to populate the numerous music festivals. Of special note is the Split festival which usually produces the best summer hits.

Croatian pop music is fairly often listened to in Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia and Montenegro due to the union of Yugoslavia that existed until the 1990s. Conversely, Bosnian singers like Kemal Monteno and Dino Merlin and Serbian Ceca, Πorde Balazevic and many others also have a large audience in Croatia.

Croatia is a regular contestant on the Eurovision Song Contest. Back in Yugoslavia, Croatian pop group Riva won the contest in 1989.

The Moreska Dance

Moreska is pronounced 'Moreska'. It means 'Moorish'. The word is derived from the Spanish adjective 'Morisco' or the Italian 'Moresco'. It is a matter of conjecture whether the dance came to the Adriatic directly from Spain through roving Spanish sailors, or from Sicily or Italy when Dalmatia formed part of the Venetian Republic whether it was originally a Moorish dance or a Spanish one, inspired by the struggle of Spanish Christians against the Moors is also debatable though the latter seems the most likely. We do know for certain that it is one of the oldest traditional European dances still performed, and that records exist of it being danced in Lerida in 1156 in a form portraying a Christian and National victory over the Moors and their expulsion from Aragon.

From the 12th century and particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries, the dance spread to many Mediterranean countries: to Italy, Corsica, Sicily, Malta, France and, through Spanish trade, to Flanders, Germany and even to England. It was subject to frequent local variations, in regard to plot, protagonists and eventually also to form. In Corsica it was danced by eighty swordsmen on each side, armed with two swords apiece, who did battle for the town of Mariana to the music of a solo violin; in Elba the engagement was between Christians and Turks, in other places between Arabs and Turks; sometimes the damsel in distress was a white maiden of royal blood, sometimes a Turkish or Moorish one of equal innocence and beauty. In Ferrara a dragon was introduced who tried to devour the damsel and there were many later versions which degenerated from the original war-dance (intrinsically a useful sword practice and 'keep-fit' class for the warriors of small island or coastal garrisons for whom good swordsmanship and alertness meant their survival) into a form of folk drama, and eventually into the dance interludes of pastoral plays and Italian opera. In Germany the Moreska, though called Moriskentanze, became a mere collection of local folk dances and in England the Morris (l.e. Moorish) dancers threw away their swords and substituted long wooden sticks which they fought with and over which they hopped. In most of the Mediterranean the Moreska survived until the end of the 18th century, and in Italy and Dalmatia till the close of the 19th.

Today, Korcula is the only island where it is still danced with real swords in its original War-Dance form and where it has enjoyed a proud and almost unbroken tradition for over four centuries, though the text, music and pattern of the dance have been slightly altered and shortened (the contest used to last for two hours!) over the years.

The introduction to the dance is a short drama in blank verse which sets the scene -- four characters recite the verses: the enemy or the Black King, his father, Otmanovic, (a kind of Balkan mediator), the Hero or the White King, and the Bula or Moslem maiden, who is a peace-maker as well as a heroine (and a possible convert to Christianity?).

The Moreska arrived in Korcula in the 16th century, at the same time as it did in Dubrovnik, most probably from Sicily or Southern Italy, via Venice. An indication of this is that two of the dance "figures" have Italian names: the "Rujer" and the "Rujer di fori via". "Ruggero" was the name of a Sicilian war-dance, a version of the Moreska, in which the Saracens are shown fighting against the Norman Prince Ruggiero d'Altavilla -- a powerful family who ruled over Sicily and Southern Italy in the 11th and 12th centuries, which suggests a possible link. There are, however, no written records of the Korculan dance until the beginning of the 18th century. Latterly and up to the first World War the Moreska was "fought" only every few years -- protagonists were often wounded and replaced by 'seconds' during the dance -- between 1918 and 1939 it was performed every year under the aegis of the Gymnastic Society of Korcula. Nowadays it is an exclusive Society (and 'club') of its own and the Moreska is performed much more frequently for the benefit of the many tourists who visit the Island. Every family in Korcula is proud to have one of its members dance in the Moreska, especially one of the key roles, which demand considerable talent and stamina. When the Black or the White Kings "retire" they are allowed to keep their crowns and these become valued family possessions.

During the second World war costumes, swords, even musical scores and instruments had all been lost in the bombing and fighting and for the first time in its history only very young lads of between twelve and seventeen were available to dance the Moreska, and they had to be taught from scratch.

It was the undefeatable and indefatigable spirit of Ivo Lozica, the town barber, and Bozo Jerirevic, a school-teacher, with the help of a local policeman, Zdravko Stanic, and Josip Svoboda the conductor of the town orchestra, that somehow got the Moreska dancing again and in a very short time the poor, thin undernourished youths were growing into splendid young men and were taking the Moreska to youth conferences and festivals at home and abroad.

National holidays

- Jan 1: New Year's Day

- Jan 6: Epiphany (probably not a holiday)

- May 1: May Day

- Jun 22: Antifascist Struggle Day

- Aug 5: National Thanksgiving Day

- Aug 15: Assumption

- Oct 8: Independence Day

- Nov 1: All Saints Day

- Dec 25: Christmas Day

- Dec 26: Boxing Day

Embassies

- Embassy of Albania in Zagreb, Croatia -- Vrhovec 231, Zagreb, Croatia. Tel: 177646 Fax: 177659

- Australian Trade Correspondence Office in Zagreb, Croatia -- Ul. Kralja Zvonimira 43, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 442885 Fax: 410071

- Australian Consulate in Zagreb, Croatia -- Hotel "Esplanade" Mihanoviaeeva 1, 1000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4566617 Fax: 4577433

- Australian Consulate in Zagreb, Croatia -- Hotel Esplanade, Mezzanine Floor, Mihanoviceva 1, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4577433 Fax: 4577907

- Consulate of Austria in Zagreb, Croatia -- Stipana Konzula Istranina 2, 51 000 Rijeka, Croatia Tel: 338554 Fax: 338554

- Embassy of the Republic of Austria in Zagreb, Croatia -- Jabukovac 39, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 427349, 427350 Fax: 424065

- Embassy of Belgium in Zagreb, Croatia -- Pantoveak 125 B I, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4578901, 4578903 Fax: 4578902

- Embassy of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Zagreb, Croatia -- Torbarova 9, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. Tel: 4683761, 4683762, 4683765 Fax: 4683764

- Embassy of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Zagreb, Croatia -- Department for Consular Affairs - Ul. Pavla Hatza 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4819418, 4819420 Fax: 4819420

- Embassy of Bulgaria in Zagreb, Croatia -- Novi Goljak 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4823336, 4823337 Fax: 4823338

- Embassy of Canada in Zagreb, Croatia -- Prilaz Gjure Dezelia #4 Tel: 4848058,4848059 Fax: 4848063 E-mail: zagrb@dfait-maeci.gc.ca

- Embassy of Chile in Zagreb, Croatia -- Raekoga 8, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4550468, 4610894 Fax: 4552054

- Embassy of the People´s Republic of China in Zagreb, Croatia -- Rusanova 13, Zagreb 10000 Tel: 223830 Fax: 2336644, 2337066

- Embassy of the Czech Republic in Zagreb, Croatia -- Savska cesta 41, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 6177246 Fax: 6176630

- Danish General Consulate in Zagreb, Croatia -- Pantovcak 35, HR-10000 Zagreb Tel: (1) 37 6 0 536, Fax: (1) 37 60 535 E-mail: danski-konzulat@zg.tel.hr

- Royal Danish Embassy in Zagreb, Croatia -- Immigration Office - Trg bana Josipa Jelaeiaea 3/II, p.o. 1054, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. Tel: 421677 Fax: 427610

- Embassy of Egypt in Zagreb, Croatia -- Tuskanac 58a, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4818426, 4818427 Fax: 425 428

- Embassy of the Republic of Finland in Zagreb, Croatia -- Berislaviceva 2/I 10000 Zagreb Croatia Tel: 4811662 Fax: 4819946

- Consulate of the Republic of Finland in Zagreb, Croatia -- Jurjevska 15, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4597333 Fax: 420 888

- Embassy of France in Zagreb, Croatia -- Schlosserove stube 5, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4818110, 4818191, 4817227 Fax: 4816 899

- Section of Consular Affairs in Zagreb, Croatia -- Gajeva 12, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4872508, 4872517 Fax: 4872 521

- Embassy of Germany in Zagreb, Croatia -- Ulica Grada Vukovara 64, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 6158100, 610 8101 Fax: 6158103

- Consulate of Germany in Split, Croatia -- Obala Hrvatskog narodnog preporoda 10/II, 21 000 Split, Croatia Tel: 362114, 362995 Fax: 362115

- Embassy of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in Zagreb, Croatia -- Vlaska 121/III, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4555310 Fax: 4551685

- Embassy of Greece in Zagreb, Croatia -- Babukiaeeva 3a, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 2335834, 2331650 Fax: 2302893

- The Papal Nunciature in Zagreb, Croatia -- Ksaverska cesta 10a, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4673996, 4673995 Fax: 4673997

- Embassy of Hungary in Zagreb, Croatia -- Krlein gvozd 11a, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 422654, 422743, 422296 Fax: 420542

- Consulate of Hungary in Rijeka, Croatia -- Riva Boduli 1, 51 000 Rijeka, Croatia Tel: 213494 Fax: 331614

- Embassy of India in Zagreb, Croatia -- Boskoviaeeva ulica 7A, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 430163, 430063 Fax: 4817907

- Embassy of Iran in Zagreb, Croatia -- Pantoveak 125 b, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4578983, 4578984 Fax: 4578987

- Consulate General of Italy in Rijeka, Croatia -- Riva 16, 51 000 Rijeka, Croatia Tel: 212454 Fax: 214308

- Vice Consulate of Italy in Split, Croatia -- Obala Hrvatskog narodnog preporoda 3, 21 000 Split, Croatia Tel: 48155, 589107 Fax: 361268

- Embassy of Italy in Zagreb, Croatia -- Meduliaeeva 22, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4846386, 4846387, 4846388 Fax: 4846384

- Embassy of Japan in Zagreb, Croatia -- Ksaver 211, 1000 Zagreb, Republic of Croatia. Tel: 4677755 Fax: 4677766

- Consulate of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Zagreb, Croatia -- Graèanska cesta 81, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 420353 Fax: 422974

- Embassy of Macedonia in Zagreb, Croatia -- Petrinjska 29/I, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 435079 Fax: 435079

- Embassy of Malaysia in Zagreb, Croatia -- Slavujevac 4A, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 427121, 426141 Fax: 422563

- Embassy of Malta in Zagreb, Croatia -- Beciaeeve stube 2, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 431635, 4677999 Fax: 431635, 4677999

- Embassy of Netherlands in Zagreb, Croatia -- Medvesecak 56, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4819533 Fax: 42420

- Royal Netherlands Consulate in Rijeka, Croatia -- Medvesecak 56, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4819533 Fax: 424205

- Embassy of Norway in Zagreb, Croatia -- Petrinjska 9/1, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 428363, 428863 Fax: 428127

- Embassy of Pakistan in Zagreb, Croatia -- Sestinski, vijenac 44, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 439522, 429023 Fax: 433654

- Consulate of Peru in Zagreb, Croatia -- Ksaverska cesta 19/II, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4677325 Fax: 670120

- Embassy of Poland in Zagreb, Croatia -- Krlein Gvozd 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4819233 Fax: 420305

- Consulate of Portugal in Zagreb, Croatia -- Trg hrvatskih velikana 3/I, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4614453 Fax: 4655166

- Embassy of Romania in Zagreb, Croatia -- Srebrnjak 150A, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 2430137 Fax: 2430138

- Embassy of Russia in Zagreb, Croatia -- Bosanska 4, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 3755038, 3755039 Fax: 3755040

- Consulate of the Republic of Slovenia in Zagreb, Croatia -- Obala hrvatskog narodnog preporoda 3, 21 000Split, Croatia Tel: 356880, 356988 Fax: 356936

- Embassy of Slovenia in Zagreb, Croatia -- Savska c. 4/IX, 110000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 6311000, 6311011 Fax: 6177236

- Consulate of Spain in Zagreb, Croatia -- Dioklecijanova I/II, Split, Croatia Tel: 343377, 343372 Fax: 343372

- Embassy of the Kingdom of Spain in Zagreb, Croatia -- Meduliaeeva 5, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4848603, 4848606 Fax: 4848605

- Embassy of the Republic of Sudan in Zagreb, Croatia -- Andrijeviaeeva 2, 110000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 3777808 Fax: 3777809

- Consulate of Sweden in Rijeka, Croatia -- Riva 16, 51 000 Rijeka, Croatia Tel: 212287 Fax: 211014

- Embassy of Sweden in Zagreb, Croatia -- Frankopanska 22, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4849322, 4849333 Fax: 4849244, 4849329

- Embassy of Switzerland in Zagreb, Croatia -- Bogoviaeeva 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4810891, 4810895 Fax: 4810890

- Royal Thai Consulate in Zagreb, Croatia -- Gunduliaeeva 18/IV, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 434982 Fax: 434982

- Embassy of Turkey in Zagreb, Croatia -- Masarykova 3/II, 10 000 Zagreb,Croatia Tel: 4855200 Fax: 4855606

- Embassy of Ukraine in Zagreb, Croatia -- Voaearska 52, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4616296, 4556128 Fax: 4553824

- Embassy of the United States of America in Zagreb, Croatia -- Andrije Hebranga 2-4, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Tel: 4555500 (8-18h), 4555281 (18-8h) Fax: 4558585, 4553126, 4550892

- Embassy of Chile in Zagreb, Croatia

- Embassy of France in Zagreb, Croatia

- Embassy of Germany in Zagreb, Croatia

- Embassy of India in Zagreb, Croatia

- Embassy of Italy in Zagreb, Croatia

- Royal Netherlands Embassy in Zagreb, Croatia

- Embassy of the United States of America in Zagreb, Croatia

- Austrian Trade Commission in Zagreb, Croatia

- Italian National Institute for Foreign Trade in Zagreb, Croatia